Angel’s Flight

UPDATED: November 2021

I went to see my beloved Angels Flight in downtown Los Angeles last week and much to my disappointment and sadness it was showing signs of neglect.

I called a fellow by the name of Gary Hall who is the General Manager for the project and was met with a rather blasé response when it came to keeping the project free of graffiti and properly maintained.

He claims that he regularly sends a maintenance crew out but as you can see from the videos and photographs this is far from the truth.

In an effort to bring this to the attention of the public and the the management, we are planning an awareness campaign via series of musical Flash Mobs along with a faux cleanup crew all set to Doors music along with select celebrity figures.

The press will be alerted before the event and a live recording will be presented on all social media outlets.

COME ON BABY LIGHT MY FIRE

ANGELS DANCE AND ANGELS DIE

“DEATH MAKES ANGELS OF US ALL

AND GIVES WINGS WHERE ONCE

WE HAD SHOULDERS SMOOTH AS RAVENS CLAWS”

The time you wait subtracts the joy

Beheads the angels you destroy

Angels fight, angels cry

Angels dance and angels die

From: We Could Be So Good Together. Jim Morrison

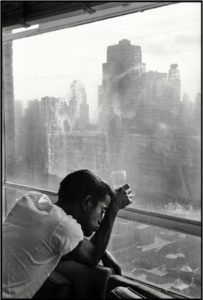

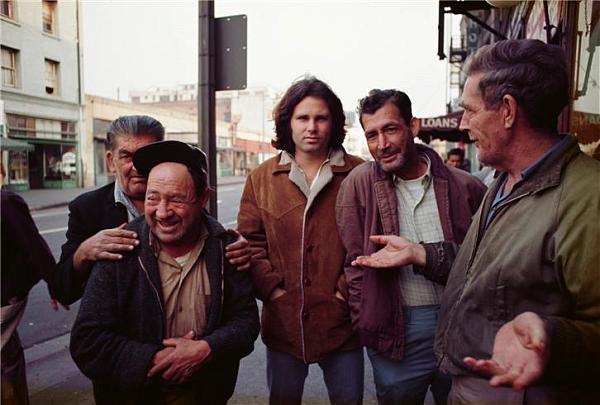

It is Sunday morning in late December of 1969, I am riding shotgun in the Blue Lady and it is raining cats and dogs. Jim was at the zenith of his rock-idol period. His celestial sphere sat directly above at High Noon.

He was also days-drunk but also acting like he was not. He was on automatic pilot stopping only to pass a bottle in a brown bag or to ask me for another cold beer sitting at my feet. He switched between radio stations playing only driving rock, his own music, and the rest of the top songs of the day.

It would be a year before his Swan Dive in Miami, and as his own eerie lyrics so fatally predicted, this rock rebel, mischievous angel would tumble from the heavens. He would become mortal, never to fly again.

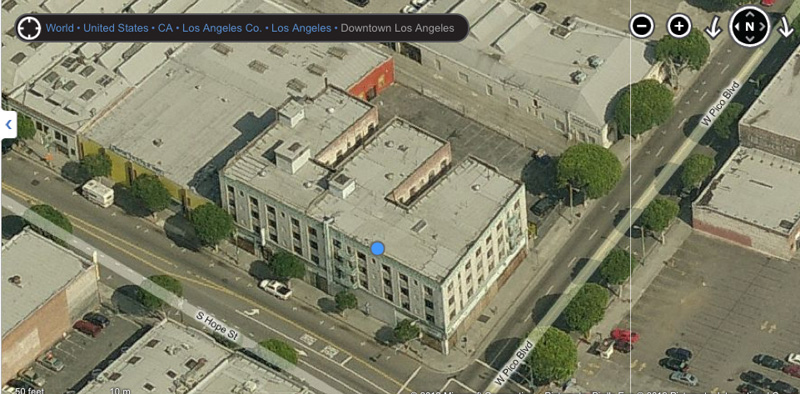

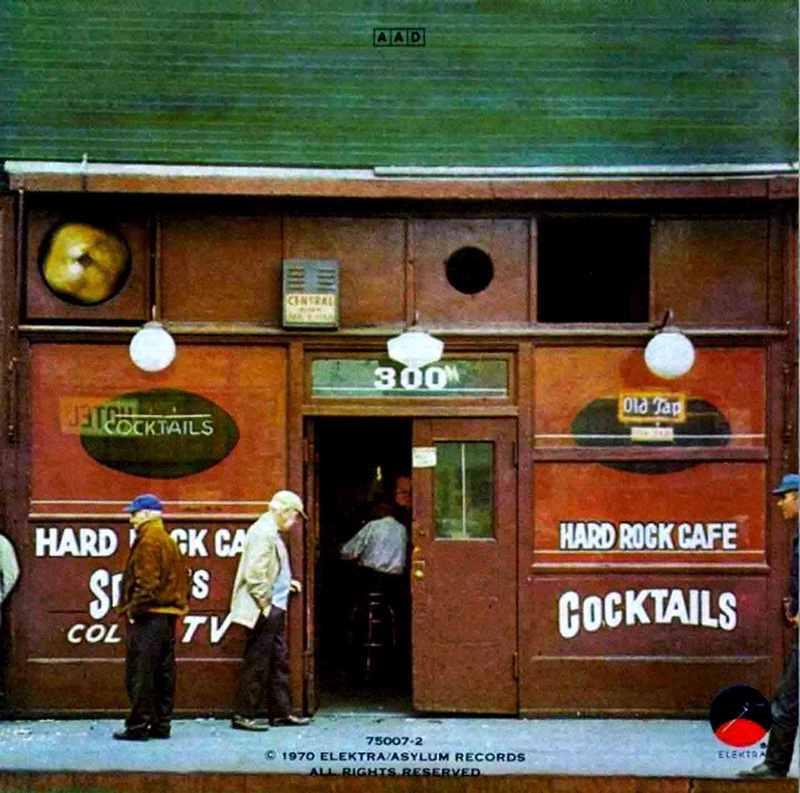

We cruised through downtown Los Angeles which at the time was still a colossal slum. A few years earlier, Bunker Hill sat in ruins peopled by the dregs of society, once a fabulous district of old victorian mansions was now rapidly dissembling in gruesome symbiosis.

The beginnings of new Los Angeles skyline had now replaced a shameful “Bowery slum” with new high rises and a swanky convention center. In the surrounding streets, it was still “those dark satanic mills”. The appalling living conditions were on par with any third world country.

I asked Jim if we could go see Angels Flight. We pulled over to the curb and sat at the top of Bunker Hill watching the deluge. He looked at me for what seemed like an eternity. Then he turned off the radio and said, “What did you say?”

I repeated, Angels Flight. It’s around here somewhere, right?

I was puzzled that he seemed so surprised. Then he said ,”How could you possibly know about Angels Flight?” Now it was my turn to be surprised. Surely he had seen it in most gangster movies or detective shows in early Los Angeles film noir. It was seen in TV shows — Dragnet, Perry Mason, and movies like Kiss Me Deadly, and even very silly movies such as The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies.

He listened intently as I rattled off the names of the very same films and TV series he also cherished as much as any historian. We talked back and forth about gangsters,villains, and heroes, movies about cowboy legends, war heroes, bad guys, and naughty girls.

“So where is Angels Flight?” I asked again.

We headed downtown where the rain was now hitting the streets like rapid gunfire with swift flowing gutters. Touch Me was blasting on the radio. The torrential gatling-gun-rain was louder.

We sat looking at Angels Flight or I should say, the site where it once rested. Jim looked over at me and said “Tt’s gone. They tore it down this summer.” We sat in silence, or to sharpen the point, “in rapt funeral amazement” .

We were both startled by the the absolute polar opposite mood we were dragged into. Scarborough Fair was playing in all its far too pleasant, feel good lyrics, “parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme”. We both contemplated visceral suicide. Jim changed the station, and soon we were released from the dreadful happiness and back to Steppenwolf’s Magic Carpet Ride’. We drove off singing at the top of our lungs in a desperate attempt to shake off the sickeningly sweet lyrics “Are you going to Scarborough Fair?”

Two years later Jim would be dead, but these memories are as vivid as they were on that day. Whenever I visit Los Angeles if I do not visit the new site it matters not for just being in proximity is as good as being there and those indelible remembrances prevail.

Twenty-seven years later August 31, 2017, the funicular railway was lovingly restored, then reopened to my delight. Just to see it running again is to take a trip back in time to the sweet never-to-be-seen-again era of silver and celluloid

ANGEL’S FLIGHT TODAY.

EROTIC POLITICIANS

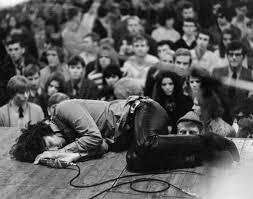

Out of the vastness of the Los Angeles Forum, its 18,000 seats filled on a December Saturday night with the cream of LA’s teenybopper set, came the insolent cry. The Doors didn’t want to do their 1967 hit; not only had they just finished their first number, but onstage with them and their 32 amplifiers were a string sextet and a brass section ready to perform new Doors music.

They got through a few more numbers, but then, with the yelling getting louder, they acquiesced. A roar of cheers and instantly the arena was aglow with sparklers lit in literal tribute. The song over, and the kids shouting for more, lead singer Jim Morrison, in a loose black shirt and clinging black leather pants, came to the edge of the stage.

“Hey, man,” he said, his voice booming from the speakers on the ceiling. “Cut out that shit.” The crowd giggled.

“What are you all doing here?” he went on. No response.

“You want music?” A rousing yeah.

“Well, man, we can play music all night, but that’s not what you really want, you want something more, something greater than you’ve ever seen, right?”

“We want Mick Jagger,” someone shouted.

“Light My Fire,” said someone else, to laughter.

It was a direct affront, but the Doors hadn’t seen it coming. That afternoon, before the concert, Morrison had said: “We’re into what these kids are into.” Driving home from rehearsal in his Mustang Shelby Cobra GT 500, he swept his arm wide to take in the low houses that stretched miles from the freeway to the Hollywood Hills. “We’re into LA. Here, kids live more freely and more powerfully than anywhere else, but it’s also where old people come to die. Kids know both and we express both.”

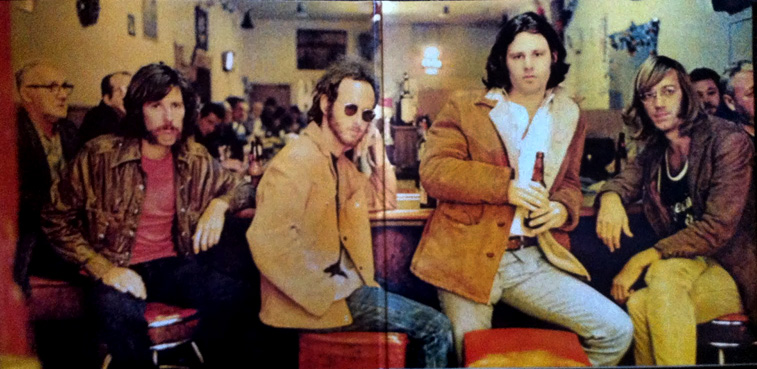

The teens had belonged to the Doors; their amalgam of sensuality and asceticism, mysticism and machine-like power had won these lushly beautifully children heart and soul, and the kids had made them the biggest American group in rock music. Now, at one of their biggest concerts, prelude to the biggest ever at New York’s Madison Square Garden in January, the kids dared laugh, even at Morrison. Not much, but they had begun.

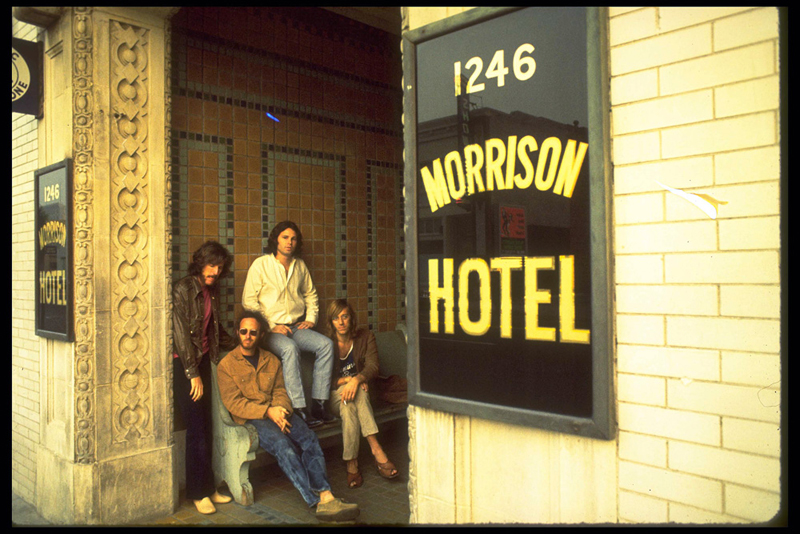

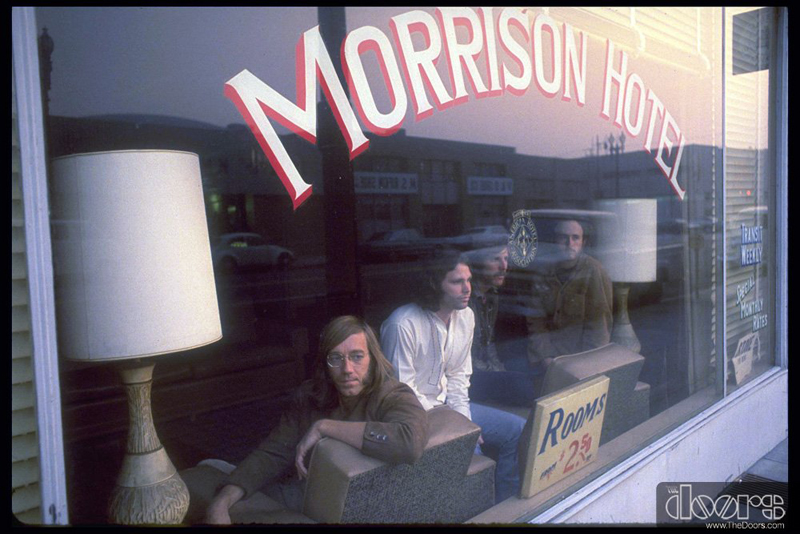

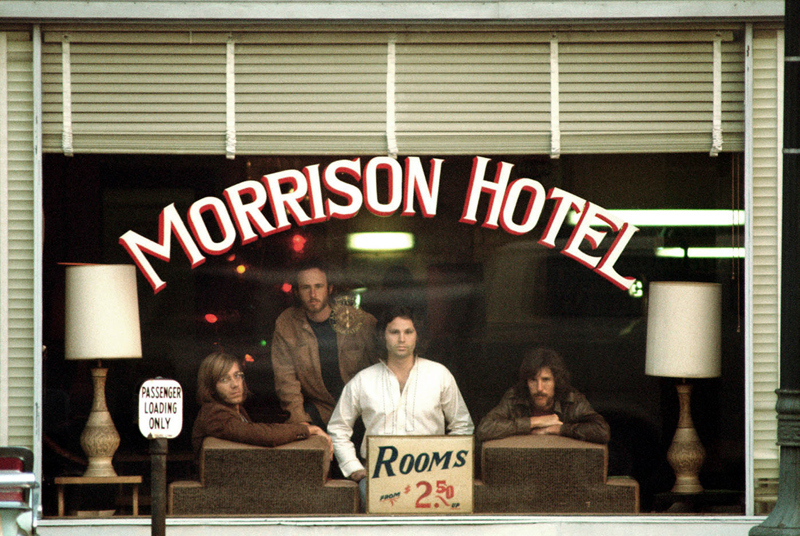

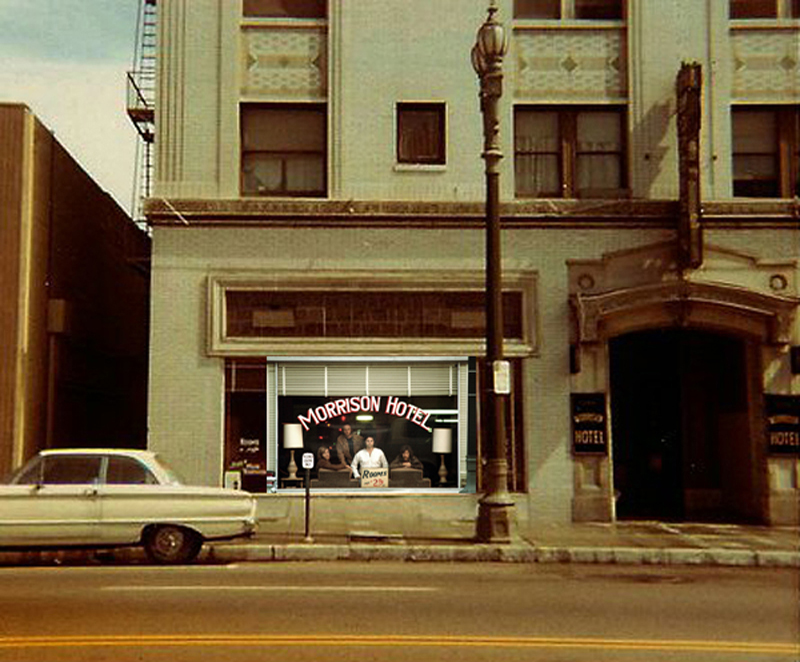

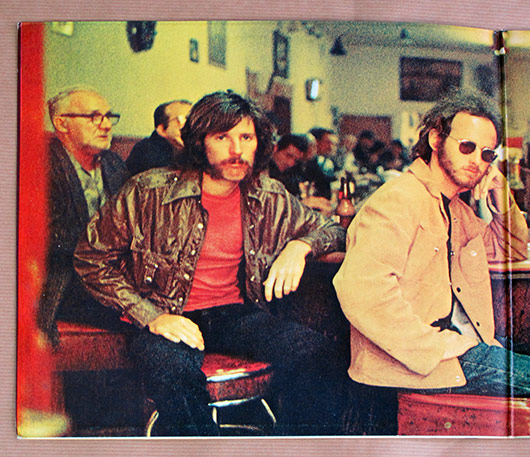

The Doors started out in LA’s early hip scene in 1965. Morrison, then 22, son of a high-ranking navy official, met organist-pianist Ray Manzarek on the beach at Santa Monica while both were making experimental films at UCLA. Drummer John Densmore and guitarist Robby Krieger became friends of Manzarek at one of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s first meditation centres in southern California. Named from a line of Morrison’s poetry – “There are things that are known and things that are unknown; in between are doors” – by early 1966 they had their first date, playing for $35 a week at a tiny and now defunct club on Sunset Strip.

While on their second job as the house band at Whisky a Go Go, working behind dozens of groups they have now eclipsed, they began to build a following, playing blues and classic rock songs with a harsh and eerie stringency.

“We were creating our music, ourselves, every night,” Morrison said, “starting with a few outlines, maybe a few words for a song that gradually accrued particles of meaning and movement. Sometimes we worked out in Venice, looking at the surf. We were together and it was good times.”

Their best songs, Crystal Ship, the diabolical The End and Light My Fire took shape in those early days while Morrison was developing the erotic style that has made him the group’s star and rock’s biggest sex symbol. He doesn’t fall off stages any more, but he writhes against the microphone stand, leaps from eyes-closed passivity into shrieking aggression, and moans sweet pain like a modern St Sebastian pierced by the arrows of angst and revelation.

Just about everybody takes him seriously: the New Haven police who last year arrested him for “giving an indecent or immoral exhibition”; the girls who rush the stage, sometimes only to get ashes flicked from his cigarette; and critics who rave in detail about “rock as ritual”. But no one takes Morrison as seriously as Morrison takes Morrison.

His stage manner, he said, unlike the acts of Elvis, Otis Redding, and Mick Jagger, with whom he is often compared, has a conscious purpose. Shyly, almost sleepily soft-spoken in private, he sees his public self as a new kind of poet-politician. “I’m not a new Elvis, though he’s my second favourite singer – Frank Sinatra is first. I just think I’m lucky I’ve found a perfect medium to express myself in,” he said during a rehearsal break, slouched tiredly in one of the Forum’s violently orange seats. Though handsome, with his pale green eyes and Renaissance prince hair, he has none of the decadent power captured in the spotligh

“Music, writing, theatre, action – I’m doing all those things. I like to write, I’m even publishing a book of my poems pretty soon, stuff I had that I realised wasn’t for music. But songs are special. I find that music liberates my imagination. When I sing my songs in public, that’s a dramatic act, not just acting as in theatre, but a social act, real action.

“Maybe you could call us erotic politicians. We’re a rock’n’roll band, a blues band, just a band, but that’s not all. A Doors concert is a public meeting called by us for a special kind of dramatic discussion and entertainment. When we perform, we’re participating in the creation of a world, and we celebrate that creation with the audience. It becomes the sculpture of bodies in action.

“That’s politics, but our power is sexual. We make concerts sexual politics. The sex starts out with just me, then moves out to include the charmed circle of musicians on stage. The music we make goes out to the audience and interacts with them, they go home and interact with the rest of reality, then I get it back by interacting with that reality, so the whole sex thing works out to be one big ball of fire.”

That analytical abandon was just right for the serious rock of the post Sgt Pepper era. After the album version of Light My Fire got heavy airplay on FM rock stations, Elektra released a shorter single that became a top 40 No 1. The Doors have followed it with a series of singles and two more albums. They have a quickly identifiable instrumental sound based on blues topped with Morrison’s strong voice and lyrics. Manzarek plays a rather dry organ, but Krieger is an aggressive guitarist and Densmore a solid and inventive drummer.

Yet as the kids in the Forum knew, they’ve never topped Light My Fire. The abandon has gotten more and more cerebral, the demonic pose more strained. The new music they wanted the crowd to like at the concert was abstract noise crashing behind a Morrison poem of meandering verbosity.

After the show, Morrison said it had been “great fun”, but the backstage party had a funereal air. And at times that afternoon, he showed that he knew their first rush of energy was running out. Success, he said, looking beat in the orange chair, had been nice. “When we had to carry our own equipment everywhere, we had no time to be creative. Now we can focus our energies more intensely.”

He squirmed a bit. “The trouble is that now we don’t see much of each other. We’re big time, we go on tours, record, and, in our free time, everybody splits off into their own scenes. When we record, we have to get all our ideas then, we can’t build them night after night like the club days. In the studio, creation is not so natural.

“I don’t know what will happen. I guess we’ll continue like this for a while. Then to get our vitality back, maybe we’ll have to get out of the whole business. Maybe we’ll all go off to an island by ourselves and start creating again.”

ROYALTIES FROM THE TOMB

Even when rock stars create more-or-less conventional families, the lines of dynastic inheritance can still break down within a generation or two.

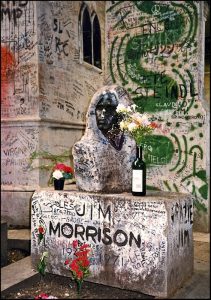

In theory, Jim Morrison, made the smart moves to ensure that his wealth – a “massive” $400,000 when he died in 1971 – transferred in an orderly fashion to his common-law wife Pamela Courson.

But because he and Courson died childless and she didn’t bother writing a will, control of his 25% stake in the Doors’ record sales and copyrights became contentious.

And now that the last of the first generation of caretakers is in her early 90s, the rights seem likely to accelerate their slide away from the people who knew and understood Morrison when he was alive.

The lesson for estate planners focused on the long term is clear: the first transfer is relatively easy to lock down, but the real work is in keeping things on track when the property shifts again decades down the road.

The truly long tail

Morrison’s lawyer is only accountable for part of the problem here.

Back in 1971, nobody predicted that the copyrights on the Doors song catalog would even still be an issue 43 years after the rock star himself was dead.

Under then-extant intellectual property law, Morrison’s lyrics would have stopped accruing royalties in 1996 and the challenge of assigning that income stream beyond that point would be academic.

However, unexpected extensions of the copyright period now mean that his literary estate remains active until at least 2041, which means putting plans in place to cover almost 40 years of further contingencies.

The legal landscape keeps changing, so the best an executor can really do is remain engaged and flexible enough to roll with unexpected developments.

A similar case can be made for the dynastic family as a moving target, and this is where Morrison should have gotten better advice.

His will left everything to Coulson, who only survived him by three years before a fatal overdose.

When her name showed up in Morrison’s will, his lawyer should have asked the follow-up questions: what happens if she dies, and does she have a will as well?

Evidently the conversation only got far enough to establish that if Coulson failed to outlive Morrison by longer than a few months, the songs and royalties they represent would revert to his brother and sister.

She survived long enough, so she inherited. But if anyone ever asked her about her own plans, nobody seems to have acted on the answers – the chain of succession died with her.

In the absence of a will, her parents inherited. His parents sued and received an ongoing stake in his legacy to ensure “parity.”

It’s clear from Morrison’s conscious decision to bypass his parents that he he didn’t want them to oversee his artistic posterity, while the Coulsons were practically strangers.

But because nobody sat down with Pamela before she died, those people ended up in control of his posthumous rights all the same.

Poetic justice or just random drift?

Doors devotees characterize Pamela’s father, who originally became artistic executor of the estate after she died, as the most eager to develop the Morrison mystique.

The Morrisons themselves seem to have been content to take a back seat and let the checks come in.

Either way, the only one of the original four parents left alive at this point is Coulson’s mother, Pearl.

She turns 91 in September, so the time left for her to weigh in on the estate is getting short. What happens when she dies?

Jim’s mom and dad have been gone since 2005 and 2008, respectively. Odds are good they bequeathed their share in the Doors to their surviving kids, which would mean the brother and sister are finally back in the loop.

On Pamela’s side, sister Judith is still alive and is likely to inherit when her mother dies.

However the beneficiaries weigh out, they’ll collectively be entitled to a 25% split of the Doors’ residual income streams alongside Robby Krieger, John Densmore and the late Ray Manzarek’s wife.

Based on a reported $3 million in annual record and download sales plus incidental publicity and memorabilia licensing, each quarter of the band may be worth $1 million a year at this point.

That’s not a tragedy, but as the slices get thinner, it becomes harder to align all the interests.

Krieger and Manzarek already alienated Densmore and the Morrison heirs by trying to cash in with a touring reunion act without consent from the other partners.

They were also eager to break Morrison’s long-standing edict against licensing the catalog to advertisers, even though the right commercial could easily quadruple or quintuple reported record sales revenue.

Apple and Mercedes were both interested in paying seven to eight figures for an ad, but both times the other partners shot the deal down as contrary to the band’s principles.

Does Jim Morrison’s sweetheart’s sister take his bohemian credo more seriously than cold hard cash? What about her kids, or his own nephews or nieces?

Sooner or later, the artistic vision that creates the music gets so diluted that entertainment becomes a business. When that happens here, you’ll hear “Riders on the Storm” and other songs used to sell cars and iPods.

And eventually, one or more interests will want to cash out for a lump sum. The more pieces the pie gets cut into, the harder it will be to negotiate a group deal – but it will get easier for an outsider to accumulate the rights piece by piece.

Unless members of the Morrison and Courson families make an effort to teach the heirs what the Lizard King wanted, he’s not going to get what he wanted.

Beyond the grave

Needless to say, Morrison could have exercised much stronger “dead hand” powers by putting his intellectual property into a trust.

That vehicle could have paid Pamela all of its income for as long as she was alive, but she wouldn’t have been able to direct its long-term strategy one way or another.

If Jim said his trust would always veto the rest of the band on licensing the songs, that’s what the trust would do.

And upon Pamela’s death, successor beneficiaries would be determined according to Jim’s dictates. Although we can’t know for sure, this would probably leave the income with his siblings today, bypassing both sets of parents and ultimately all of the Coursons.

The beneficiaries would be free to do as much or as little estate planning as they like in order to assign their own assets. The Doors lyrics would enjoy the closest thing to immortality the law allows.

And as the law changes, a well-constructed trust would be able to change with it while leaving its core mandate untouched.

If intellectual property protection stretches out even further, a Morrison trust would have the power to plan to be around in 2050 and beyond.

With the right trustees, the vehicle could also adapt to shifts in the marketing environment, sidestepping the land grab over “peripheral” merchandising that has troubled the Jimi Hendrix estate, for example.

There will probably be scenarios we don’t even know how to forecast yet, let alone manage. Jim Morrison couldn’t even see his wife’s death coming. A trust can evolve with the times.

UPDATE..

Pearl “Penny” Courson

Passed away peacefully Friday July 11, 2014 at her home in Santa Barbara, CA after a long battle with cancer at the age of 90.

Born September 14, 1923 in Chicago, IL, Penny was the daughter of the late Paul Schmidt of Vienna, Austria and the late Margaret Jarvis Schmidt of Illinois.

She is survived by her daughter Judith Courson Burton, granddaughter Emily Burton and husband Chris McGillin, grandson James Burton and wife Deja Rabb Burton, and her great grandchildren Everett, Simone, and Colette. She was preceded in death by her daughter Pamela Courson Morrison and husband Columbus “Corky” Courson.

A child of the depression Penny overcame tough circumstances. After she married Corky they traveled the world. She was a connoisseur of the arts and worked as an interior designer. She was a homemaker and great cook who loved to entertain for family and friends. Penny was a staunch liberal with a feisty personality.

She loved her Bichon Frisé Lola and her dearest friend Jaime Camargo, who cared for her and her husband when they took ill.

Penny’s ashes will be interred next to the love of her life, her husband of 64 years. Memorial services will take place at the Santa Barbara Cemetery chapel on August 16th at 1pm.

In lieu of flowers please consider donating to the Jim Morrison Film Award at UCLA or The Santa Barbara Hospice, which was very helpful in her last days.

– See more at: http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/newspress/obituary.aspx?pid=171936358#sthash.kvfsPYv7.dpuf

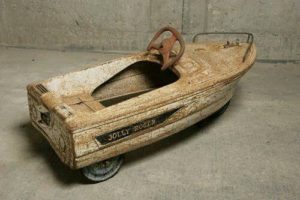

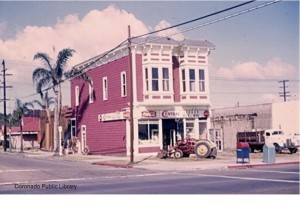

YOU KNOW YOU GREW UP IN CORONADO WHEN – REDUX

We ran this story back in 2010 and much to my delight. Coronado’s who have left here never to return still read about the way we lived. As you will read in the story and the post’s and comments section, friends are still trying to locate each other to renew old memories of precious times gone by.

A.R. Graham (Editor)

YOU KNOW YOU GREW UP IN CORONADO WHEN

Excerpts from the Facebook blog exclusively for those of us who grew up in Coronado:

YKYGUICWhen…

Does anybody remember the reverend (I think it was Reverend Brown) of the Episcopal Church, when he dyed his hair blonde and bought a corvette? This was probably back in the 50s? He was the talk of the town. That was my church growing up — still a beautiful church. – Maureen Rutherford Nieland

Does anybody remember the reverend (I think it was Reverend Brown) of the Episcopal Church, when he dyed his hair blonde and bought a corvette? This was probably back in the 50s? He was the talk of the town. That was my church growing up — still a beautiful church. – Maureen Rutherford Nieland

That’s a hoot! We could have used him over at Graham Memorial. Carson was like a raven. – Suzi Lewis

Oh, I remember him driving that car around town, LOL! – Helen Nichols Murphy Battleson

N/Ax jonnybvd@gmail.com 68.7.250.52 |

I’m looking to get a hold of Ken Brown, thanks! |

| Ken Brown 800ozbrown@gmail.com 75.16.34.40 |

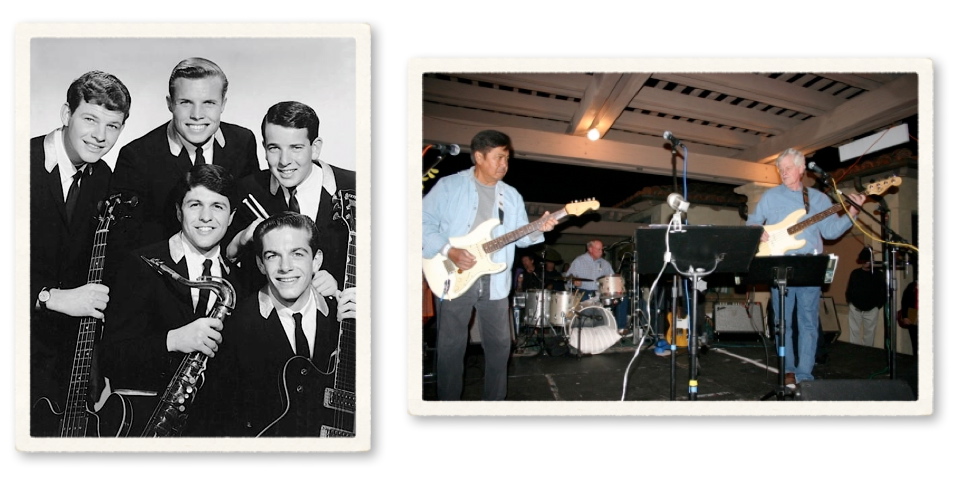

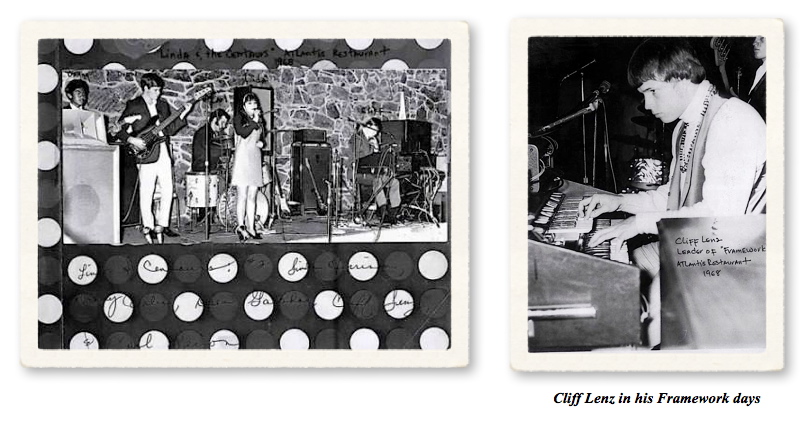

Would you believe….for the 50th CHS reunion the ‘Centaurs’ put it together one more time. Drew Gallahar (Base & Vocals/Santee) coordinated a rehearsal studio in San Diego. Surprisingly to us, sound was good and we decided to show up for the reunion. Good thing since Cliff Lenz and myself were in the class of ’64.

We had Bill Lamden (Sax,Flute,Base & Vocals/San Diego), Danny Orlino (Lead Guitar, Base & Vocals/ Guam), Ken Brown (Drums & Weird Noises/ Westlake Village), Drew Gallahar (Base, Guitar & Vocals) and the glue that brought us together, Mr. Cliff Lenz (Piano, Organ, Guitar, Base & Vocals/Seattle). We were extremely excited when Mike Seavello (Tambourine/San Diego) agreed to coordinate Sound, Equipment and our sanity checks. For 50+ years out…. we didn’t sound bad and we all had a great time. Just wanted to thank all that supported our musical efforts throughout the years. They were glorious times for each of us and hope we represented good times for you as well. |

Original Members: Cliff Lenz: keyboards, lead guitar

Rick Thomas: lead guitar

Doug Johnson: bass

Pat Coleman: drums

“The Centaurs” by Cliff Lenz: Funny how a love affair with rock and roll and a seven year odyssey of performing, recording, road trips, and opening for some of the biggest names in rock can begin with just a casual meeting between two high school kids. In the fall of 1962, a classmate and friend of mine at Coronado High, Doug Johnson, said there was a new student named Rick Thomas who played electric guitar and that we should meet. I had a Les Paul Jr. and a breadbox size amp and thought that two guys could sound a lot more like the Ventures than just one guy. So I called Rick and we got together at Doug’s house with our guitars for a jam session. Miracle of miracles, we could actually play something together that didn’t sound half bad, the Venture’s tune “The McCoy”, E, A, and B7th and lots of open string melody notes, but what the hell it was a start and it was a thrill. I’m sure that it’s a thrill for all young musicians who, never having played with someone else, experience for the first time what collaborative music making can be.

We started practicing on a weekly basis putting a repertoire together. Pat Coleman became our first drummer and we enlisted Doug Johnson to play bass. Having no prior musical experience, it was a little too much for Doug and he politely resigned from the band after a few weeks. Not long thereafter the (now) trio was asked about playing for an after-football game dance. Assistant Principal, Mr. Oliver, wanted to make an announcement over the school PA that a band would be performing but we didn’t have a name. He actually suggested we call ourselves Rick and the Shaws or Cliff and the Dwellers!We had been thinking about possible names. At the time, the Air Force had rolled out its new ballistic missile, the Atlas Centaur – That’s It! Call ourselves the Centaurs and every time they fire one of those babies off, we get free publicity. It was decision time in the principal’s office, and so the group was officially launched with Mr. Oliver’s announcement that the “Centaurs” would be playing that night. I think we had maybe fifteen tunes and played everyone of them three times, but we made it through the gig without a single tomato flying toward the stage. Another thrill and we were hooked.

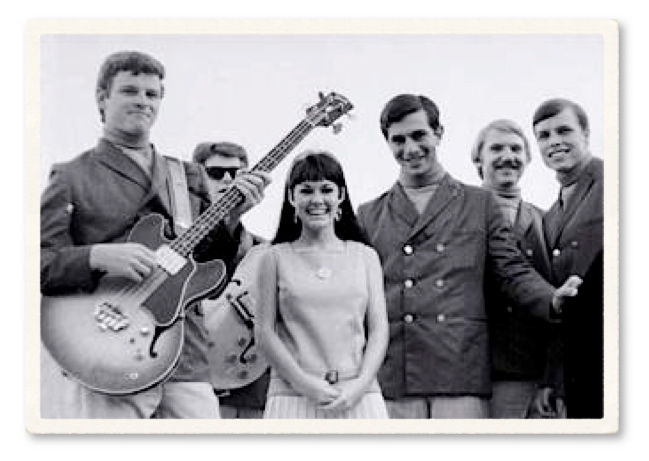

The new venture would include the frequent addition and deletion of personnel. (This is not necessarily in chronological order).We added a girl singer, Clair Carlson, and saxophonist, Randy Chilton. Kenny Brown became our new drummer with the prettiest pearl Ludwig drum set in San Diego. Drew Gallahar (a guitarist and trumpet player in the CHS stage band) joined us on bass. I got a Fender Strat and Bandmaster amp. Not to be outdone, Rick got a Fender Jaguar and Showman 15 amp and a Fender reverb unit! We got the gig as the house band at what would become the legendary Downwind Club – the Junior Officer’s Club on North Island where we played for six years barely keeping our heads above the oceans of beer served every Sunday. A wonderful saxophonist from La Jolla, Bill Lamden, replaced Chilton. For a time, Janie Seiner was our vocalist. There were dances, concerts, and car shows all over San Diego, and we even played for a change-of-command party at North Island with more captains and admirals than you could count. A major thrill was recording a couple of surf tunes in the United Artists Studio in Hollywood, a session that was produced by Joe Saracino, who had been the producer of the Ventures. We also played on the Sunset Strip in the summer of ’66 in the same club where the Doors became famous.

Rick left the group late in ’66 and was replaced by Danny Orlino. The rest of us were now at San Diego State and Danny was still at CHS. He was a truly gifted player. Bob Demmon, longtime CHS band director and rock guitarist with the famous surf group, the Astronauts, once told me that Danny was maybe the finest guitarist he had ever known personally. I now doubled on guitar and organ. I think we were the first rock group in San Diego to use a cut down Hammond. The keyboards were in one box and the guts in another for portability. I also invested in a Leslie speaker, which really enhanced our sound.

From ’62 to ’67, the music had morphed from Pop to Surf to R&B to Psychedelic. We now had a new chick singer, Linda Morrison (she lived in San Diego), a great talent who became a real driving force with her powerful vocals. Not bad to look at either. She later became Miss San Diego. Steve Kilajanski took over on sax for awhile. We also now had an agency booking engagements for us, Allied Artists of San Diego, and we joined the musicians’ union. Kenny Brown became our manager giving way to several new drummers, all excellent players – Kenny Pernicano, Rick Cutler, the late Paul Bleifuss (formerly with the great S.D. band, the Impalas), Carl Spiron (who played with one of San Diego’s all time great groups, Sandi and the Accents/Classics), and later Terry Thomas.

With great reluctance in 1969, I left my last band (Bright Morning) and my long-time guitar buddy Danny Orlino to head north to go to graduate school at the University of Washington. Danny left San Diego and has been a famous guitarist and singer in Guam for many years. Kenny Brown converted his band manager skills and keen business sense into a successful real estate and property management career in the Los Angeles area. Bill Lamden became a dentist. Drew Gallahar still has his hands all over guitars but now he makes them. He’s a guitar builder at the Blue Guitar in Mission Valley. I had a 20-year career as a television producer and the host of “Seattle Today” on the NBC affiliate in Seattle, but I was also composing and performing music at the same time. Along the way I received an Emmy for composing the theme music for the Phil Donahue Show. I have returned to music as a guitar and piano teacher in the Seattle area. Sadly, Rick Thomas died of cancer in 2004 after a career as an electrical systems maintenance engineer. I visited him in Chico, CA a few months before he passed away. We got out the guitars and played and reminisced. A few months after he died, his parents sent me his guitar, which I will always treasure. It’s an uncommon Fender model called the Coronado.

Thanks to all those of you who listened and danced to our music over the years. It was a great party! (Cliff Lenz, co-founder/leader- the Centaurs)

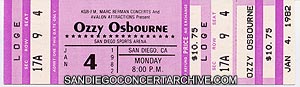

“The Centaurs” by Ken Brown: The Centaurs rock ‘n’ roll band from Coronado during the 60s meant something special because “The Centaurs” were part of the 60s Rock ‘n’ Roll Revolution. I can remember an article in the Coronado Islander, our high school paper, which pictured the Centaurs success on par with the Beatles. They were riding high and so were we. When you are young, talented, and restless, the imagination becomes your reality. We were on top of the world, our world, and it was great fun for all who participated. We went from playing at Sea World to the Downwind Club to All Night High School Parties to our own Dance concerts. A highlight was the Centaurs opening for ‘The Doors’ at Balboa Stadium. The participants had their own special role for they too were part of the 60s Rock ‘n’ Roll Revolution.

I can safely say that I would not trade a moment of this musical bonanza for any other. We were living life at a fast pace with all the trimmings. Local people knew we were the Centaurs. We carried it wherever we went. We were young talented musicians (all in the local musicians’ union) who had set a new stage and pace for rock and roll. We had the 62 + 64 Chevy 327 Impalas, the Delorean, the Lotus ,and Hemi engines, and a bunch of other hot cars of the time. The Centaurs were sexy with strapping lads and foxy singers. If you were not in the ‘mood’ before our event inevitably you left in the ‘mood’. And that’s my point.

During our 25th Centaur Reunion at the Coronado Women’s Club, we had an array of people, some family, others were supporters with their special memories of what “The Centaurs” did for them. We brought the new 60s sound to Coronado and all its surroundings. We opened the musical doors for our generation. We may have never competed with the Beatles, but we sure promoted their music, along with the Rolling Stones, and a whole lot more Legendary Rock Bands of our time. Can’t have much more fun than that because “We lived the Dream”. (Ken Brown, Drummer and Business Manager of “The Centaurs” and “Framework” from Coronado)

After publishing we received this great comment from Cliff Lenz, original member of The Centaurs:

Thanks for putting the Centaurs in the Rock ‘n’ Roll issue of the Coronado Clarion. (And first up no less!) A side note to the article I thought you’d be interested in- my father was a navy officer- graduated in the same class as Admiral Stephen Morrison from the Naval Academy (class of ’41). They were life long friends and ended up retiring together in Coronado. When I found out that he was the father of Jim….I was excited about the opportunity to ask him about his superstar son. However, my mother warned me to never bring the subject up with his parents as he was persona non grata within the family. The picture of the Admiral in the Academy ’41 Yearbook looks like Jim with a flat-top!

Another sidebar- We opened for the Doors in the old Balboa Stadium in July ’68. Amazing concert- 25,000 stoned/screaming fans. Years later Oliver Stone comes out with “The Doors” with Val Kilmer as Jim Morrison. My stock went up with my two sons when I told them that their dad’s band opened for a Doors concert in San Diego. A few years later my son, at the University of Oregon, told me that he was walking to class with a girl friend and the movie came up in the conversation.

Trying to impress her he reported that his dad had a band that opened for the Doors at a big stadium concert. She said: “Cool, My dad was actually in the Doors!” Turns out she (believe her first name was Kelly) was the daughter of drummer John Densmore!

As they say- small world.

Thanks again for the inclusion of my old band in your magazine- I dearly miss those days……… Coronado and the music of the ’60’s.

Regards,

Cliff Lenz

The Night of the Lizard King

The Night Of The Lizard King

A Ghost Rock Opera in three acts

Written By: Alan Graham

ACT I

SCENE I. Pacific ocean

Dec 7th 1941

Enter Admiral Morrison singing.

ADMIRAL

Grandma love a sailor

who sailed the frozen sea.

Grandpa was a whaler

And he took me on his knee.

He said, “Son, I’m going crazy

From livin’ on the land.

Got to find my shipmates

And walk on foreign sands.”

This old man was graceful

With silver in his smile.

He smoked a briar pipe and

He walked four country miles.

Singing songs of shady sisters

And old time liberty.

Songs of love and songs of death

And songs to set men free.

Yea!

I’ve got three ships and sixteen men,

A course for ports unread.

I’ll stand at mast, let north winds blow

Till half of us are dead.

Land ho!

Well, if I get my hands on a dollar bill,

Gonna buy a bottle and drink my fill.

If I get my hands on a number five,

Gonna skin that little girl alive.

If I get my hand on a number two,

Come back home and marry you, marry you, marry you.

Alright!

Land ho!

Work In Progress

Florence Jenkins

Florence Foster Jenkins, born Nascina Florence Foster (July 19, 1868 – November 26, 1944), was an American socialite and amateur soprano who was known and mocked for her flamboyant performance costumes and notably poor singing ability.

Despite (or perhaps due to) her technical incompetence, she became a prominent musical cult figure in New York City during the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s. Cole Porter, Enrico Caruso, and other celebrities were loyal fans. The poet William Meredith wrote that what Jenkins provided ” … was never exactly an aesthetic experience, or only to the degree that an early Christian among the lions provided aesthetic experience; it was chiefly immolatory, and Madame Jenkins was always eaten, in the end.”

Nascina Florence Foster was born July 19, 1868, in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, the daughter of Charles Dorrance Foster (1836–1909), an attorney and scion of a wealthy land-owning Pennsylvania family. Her mother was Mary Jane Hoagland (1851–1930).[2][3][4][5][6] Her one sibling, a younger sister named Lillian, died at the age of 8 in 1883.[7][8]

Foster said she first became aware of her lifelong passion for public performance when she was seven years old.[6] A talented pianist, she performed in her youth at society functions as “Little Miss Foster”,[1] and gave a recital at the White House during the administration of President Rutherford B. Hayes.[6] After graduating from high school, she expressed a desire to study music in Europe. When her father refused to grant his permission—or the necessary funds—she eloped with Dr. Frank Thornton Jenkins (1852–1917) to Philadelphia, where they married in 1885.[8] The following year, after learning that she had contracted syphilis from her husband, she terminated their relationship and reportedly never spoke of him again. Years later, Florence asserted that a divorce decree had been granted on March 24, 1902, although no documentation of that proceeding has ever surfaced.[9] She retained the Jenkins surname for the remainder of her life.

After an arm injury ended her career aspirations as a pianist, Jenkins gave piano lessons in Philadelphia to support herself; but around 1900, she moved with her mother to New York City.[6] In 1909, Jenkins met a British Shakespearean actor named St. Clair Bayfield, and they began a vaguely-defined cohabitation relationship that continued the rest of her life.[10] Upon her father’s death later that year,[8] Jenkins became the beneficiary of a sizable trust, and resolved to resume her musical career as a singer, with Bayfield as her manager.[11] She began taking voice lessons and immersed herself in wealthy New York City society, joining dozens of social clubs. As the “chairman of music” for many of these organizations, she began producing lavish tableaux vivants—popular diversions in social circles of that era.[1] It was said that in each of these productions, Jenkins would invariably cast herself as the main character in the final tableau, wearing an elaborate costume of her own design.[6] In a widely republished photograph, Jenkins poses in a costume, complete with angelic wings, from her tableau inspired by Howard Chandler Christy‘s painting Stephen Foster and the Angel of Inspiration.[12]

Jenkins began giving private vocal recitals in 1912, when she was in her early forties.[11] In 1917, she became founder and “President Soprano Hostess” of her own social organization, the Verdi Club,[2][13] dedicated to “fostering a love and patronage of Grand Opera in English”. Its membership quickly swelled to over 400; honorary members included Enrico Caruso.[1] When Jenkins’ mother died in 1930, additional financial resources became available for the expansion and promotion of her singing career.

According to published reviews and other contemporary accounts, Jenkins’ talent at the piano did not translate well to her singing. She is described as having great difficulty with such basic vocal skills as pitch, rhythm, and sustaining notes and phrases.[15] In recordings, her accompanist Cosmé McMoon can be heard making adjustments to compensate for her constant tempo variations and rhythmic mistakes,[16] but there was little he could do to conceal her inaccurate intonation. She was consistently flat, and sometimes deviated from the proper pitch by as much as a semitone. Her diction was similarly substandard, particularly with foreign-language lyrics. The technically challenging songs she selected, well beyond her ability and vocal range, emphasized these deficiencies.[15] The opera impresario Ira Siff dubbed her “the anti-Callas.” “Jenkins was exquisitely bad”, he said, “so bad that it added up to quite a good evening of theater … She would stray from the original music, and do insightful and instinctual things with her voice, but in a terribly distorted way. There was no end to the horribleness … They say Cole Porter had to bang his cane into his foot in order not to laugh out loud when she sang. She was that bad.”[10] Nevertheless, Porter rarely missed a recital.[17]

The question of whether “Lady Florence”—as she liked to be called, and often signed her autographs[10]—was in on the joke, or honestly believed she had vocal talent, remains a matter of debate. On the one hand, she compared herself favorably to the renowned sopranos Frieda Hempel and Luisa Tetrazzini, and seemed oblivious to the abundant audience laughter during her performances.[18] Her loyal friends endeavored to disguise the laughter with cheers and applause; and they often described her technique to curious inquirers in “intentionally ambiguous” terms—for example, “her singing at its finest suggests the untrammeled swoop of some great bird”—which served only to intensify public curiosity.[19] On the other, Jenkins refused to share her talents with the general public, and was clearly aware of her detractors. “People may say I can’t sing,” she once remarked to a friend, “but no one can ever say I didn’t sing.”[1] She went to great lengths to control access to her rare recitals, which took place at her apartment, in small clubs, and once each October in the Grand Ballroom of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel. Attendance, by personal invitation only, was restricted to her loyal clubwomen and a select few others. Jenkins handled distribution of the coveted tickets herself, carefully excluding strangers, particularly music critics. Favorable articles and bland reviews, published in specialty music publications such as The Musical Courier, were most likely written by her friends, or herself.[6] Despite her careful efforts to insulate her singing from public exposure, a preponderance of contemporary opinion favored the view that Jenkins’ self-delusion was genuine. “Florence didn’t think she was pulling anyone’s leg,” said opera historian Albert Innaurato. “She was compos mentis, not a lunatic. She was a very proper, complex individual.”[10]

Her recitals featured arias from the standard operatic repertoire by Mozart, Verdi, and Johann Strauss (all well beyond her technical ability); lieder by Brahms; Valverde‘s “Clavelitos” (“Little Carnations”, a favorite encore); and songs composed by herself and McMoon.[1] As in her tableaux, she designed her own elaborate costumes, often involving wings, tinsel, and flowers, to complement her performances. During “Clavelitos”, she would throw flowers into the audience from a basket (on one occasion, she hurled the basket as well) while fluttering a fan.[20] After one “Clavelitos” performance, the audience cheered so loudly that Jenkins asked the audience to return the flowers; she replaced them in her basket and performed the song again.

Once, when a taxi in which she was riding collided with another car, Jenkins let out a high-pitched scream. Upon arriving home, she went immediately to her piano and confirmed (at least to herself) that the note she had screamed was the fabled “F above high C”—a pitch she had never before been able to reach. Overjoyed, she refused to press charges against either involved party, and even sent the taxi driver a box of expensive cigars.[21][10] McMoon said neither he “nor anyone else” ever heard her actually sing a high F, however.[17]

At the age of 76, Jenkins finally yielded to public demand and booked Carnegie Hall for a general-admission performance on October 25, 1944.[15] Tickets for the event sold out weeks in advance; the demand was such that an estimated 2,000 people were turned away at the door.[17] Numerous celebrities attended, including Porter, Marge Champion, Gian Carlo Menotti, Kitty Carlisle and Lily Pons with her husband, Andre Kostelanetz, who composed a song for the recital. McMoon later recalled an “especially noteworthy” moment: “[When she sang] ‘If my silhouette does not convince you yet/My figure surely will’ [from Adele’s aria in Die Fledermaus], she put her hands righteously to her hips and went into a circular dance that was the most ludicrous thing I have ever seen. And created a pandemonium in the place. One famous actress had to be carried out of her box because she became so hysterical.”[18]

Since ticket distribution was out of Jenkins’ control for the first time, mockers, scoffers, and critics could no longer be kept at bay. The following morning’s newspapers were filled with scathing, sarcastic reviews that devastated Jenkins, according to Bayfield.[6] “[Mrs. Jenkins] has a great voice,” wrote the New York Sun critic. “In fact, she can sing everything except notes … Much of her singing was hopelessly lacking in a semblance of pitch, but the further a note was from its proper elevation the more the audience laughed and applauded.” The New York Post was even less charitable: “Lady Florence … indulged last night in one of the weirdest mass jokes New York has ever seen.”

Five days after the concert, Jenkins suffered a heart attack while shopping at G. Schirmer‘s music store, and died a month later on November 26, 1944, at her Manhattan residence, the Hotel Seymour. She was buried next to her father in the family crypt in Pennsylvania.

A Man/Woman To Go To The Well With By: Alan Graham

One of the most poignant lines from the old country song “Old dogs and Children and Watermelon Wine” by Tom T. Hall song “Friends are hard to find, when they discover that your down”, is quite often so, especially in times of crisis. It is only the fully faithful who can, and do, hang in there with you in your time of need. Others have their own problems and certainly do not want to take on another burden, so, they move away or ignore it so it will go away on it’s own.

The old saying “He is a man to go to the well with” is someone originally meant to literally accompany someone outside the safety of a stockade or safe perimeter in a time of siege during the days of Indian warfare. So a man you could or would GO TO THE WELL WITH was someone you had the utmost confidence in, admiration and highest regard for – often a highly trusted longtime friend.

I am blessed to have several friends of such noble pedigree, and one in particular is actually “A Woman To Go To The Well With”.

Three times she has saved my life, literally, and continues to watch over me often preventing me from going in the wrong direction and steering me away from potential missteps.

If you are lucky enough to have even one such loving loyal friend, treasure them and always remember, that this precious soul is “true like ice, like fire” as solid as ice and like an eternal flame that can never be extinguished.

Old Dogs And Children And Watermelon Wine Written By: Tom T. Hall

He said I turned sixty five about eleven months ago

I was sittin’ in Miami pourin’ blended whiskey down

When this old gray black gentleman was cleanin’ up the lounge

The guy who ran the bar was watching Iron sides on TV

Uninvited he sat down and opened up his mind

On old dogs and children and watermelon wine

Ever had a drink of watermelon wine he asked

He told me all about it though I didn’t answer back

But old dogs and children and watermelon wineHe said women think about they selves when menfolk ain’t around

And friends are hard to find when they discover that you’re down

He said I tried it all when I was young and in my natural prime

Now it’s old dogs and children and watermelon wine

God bless little children while they’re still too young to hate

When he moved away I found my pen and copied down that line

Bout old dogs and children and watermelon wineI had to catch a plane up to Atlanta that next day As I left for my room I saw him pickin’ up my change

That night I dreamed in peaceful sleep of shady summertime

Of old dogs and children and watermelon wine

Restaurant Row

Showing regret for making the wrong decision is no longer a behavioral trait exclusive to humans, as rats too feel sorry for not making the right choice, a new study suggests.

As part of the study, researchers conducted a task named “Restaurant Row,” in which they allowed rats to enter chambers containing different food options. And, as the rats were given only a limited amount of time to make a choice, they would sometimes pick a bad meal over a good one, and then look back at the chamber with the food they liked and be prepared to wait longer for another chance to sample their desired food.

According to the study, published in Nature Neuroscience on Sunday, the rats’ willingness to wait for their ideal choice implied that they had individual preferences. In addition, the researchers also examined the rats’ brain activity, which helped them conclude that the animals indeed experienced regret over the decisions they made while choosing their food.

“In humans, a part of the brain called the orbitofrontal cortex is active during regret. We found in rats that recognized they had made a mistake, indicators in the orbitofrontal cortex represented the missed opportunity,” Redish said. “Interestingly, the rat’s orbitofrontal cortex represented what the rat should have done, not the missed reward. This makes sense because you don’t regret the thing you didn’t get, you regret the thing you didn’t do.”

The researchers believe that the study’s findings will help them better understand why humans act a certain way and how the feeling of regret affects their decision making. The researchers also said that other mammals may also have the ability to feel regret because they have brain structures similar to those of rats and humans, LiveScience reported.

“Regret is the recognition that you made a mistake, that if you had done something else, you would have been better off,” Redish said. “The difficult part of this study was separating regret from disappointment, which is when things aren’t as good as you would have hoped. The key to distinguishing between the two was letting the rats choose what to do.”

NAUGHTY! NASTY! NIKE & MIKEY

An Editorial By: Alan Graham

Recently I bought some sweat pants and I chose NIKE only because they were on sale, a great deal I thought until that is, a friend said “You bought NIKE ?”.

And why not? said I.

My friend looked at me quizzically, haven’t you heard, anyone who loves dogs will never by NIKE ever again because of Michael Vic?.

I had forgotten that in one of the most craven maneuvers in modern times NIKE had made a deal with the DEVIL, namely one Michael Vic. Nike re-signed Philadelphia Eagles quarterback to an endorsement deal, nearly four years after dropping him amid his legal troubles.

Being a dog lover I was deeply angered to see such a low life being rewarded after a slap on the wrist.

I have vowed never to by NIKE products, and urge all those who love animals to BOYCOT and to spread the word, and even though it has been forgotten by many, these monstrous acts are still being perpetrated.

I will never forgive Vick for his callous treatment of defenseless animals and I urge everyone to do the same.

Boycott Nike. Just do it. Here are some ways to take action:

1. Let Nike know you disapprove of their decision to endorse Michael Vick. There is a Facebook page dedicated to the cause with over 14,000 supporters.

Call Nike: 800-344-6453. Choose option 5, then option 9.

2. Let the New York Jets hear your voice. Make your opinion matter. Contact a NY Jets representative at 800-469-5387 or at their Florham Park training facility at 973-549-4800.

3. Buy elsewhere. The sportswear, sportsgear, and athletic shoe trade is a billion dollar industry with stiff competitors. There is a plethora of impressive, quality gear that can be purchased without the weight of ethical guilt. There are many deserving companies engaging in hard work that deserve our support. Support companies that endorse fair market practices and decent role models. Do your research. Stand behind positive energy and good vibes.

4. Explain your consumer choices to your children. Teach them consumer power young. Arm them with the information to understand the dangers in putting your money behind poor leadership. Be your child’s own role model of leadership and intelligence.

5. End animal abuse. Donate your time or money to your local animal shelter. Eleventh Hour Rescue is an admirable local organization. Buy the organization’s shirts that benefit charity rather than Nike shirts. Consider fostering a pet, donating pet food, or rescuing an abused animal.

A Diamond In The Heart

My own medical report By. Alan Graham.

If you had a heart attack in the 1950s, the average doctor was ill equipped treat it. Back then, doctors knew very little about how to treat heart attacks and as a consequence, could do very little to save patients lives.

My Coronado practitioner Dr. James Mushovic, (Merlin) once told me ” All we did back then was make them as comfortable as possible by leaving them in a darkened room surrounded by ice packs, short of that, it was pretty much wait and see if they recovered, or not

Today we are lucky to live in a time where futuristic advances in heart surgery and treatment are beyond amazing.

It is 10 am on Saturday morning and a group of San Diego’s finest heart specialist are in video conference. What follows is a discussion/lecture concerning the newest advances in surgery such as atrial fibrillation (AFib) from cardiovascular surgeons and other heart specialists. AFib symptoms, diagnosis and advanced treatment options, including minimally invasive procedures designed to reduce the high risk of stroke associated with the condition. The old school heart surgeons are now a thing of the past, light years away in fact.

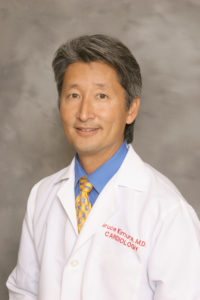

I had a heart attack in 2006 and was lucky enough to be in the care of Dr. Bruce Kimura a Coronado heart specialist. At that time my old country doctor, James Mushovic, told me that Dr. Kimura was the best he had ever seen and that I could not be in better hands. He was part of the respected Dr. Paul Phillips’ team, and as Dr. Mushovic had predicted, he would become on of the top heart specialists in the country.

Fast forward to today, and I find myself in need of a serious tune up to my 1944 model ailing heart. When I told Dr William B. Davis my country doctor for seen years, without a word he wrote a referral for Dr Ali Salmi, and the San diego Heart and Vascular Associates saying “This team is Nuli Secondi” (second to none.)

Enter Dr. Ali Salami, another brilliant heart surgeon, who is now part of the same team. The procedure was flawless, with a top team of professionals preparing me, I felt like a VIP.

After my having an angiogram, Dr Salami found that the main artery had a 90% blockage; and when he tried to implant a stent, the blockage was impossible to penerate without “heavy equipment”. (I had awful visions of being assaulted by a forty-foot drill operated by the angry visage of my dead mother-in-law.)

Dr. (Mr. Cool) Salami assured me matter of factly that it would be “a piece of cake.” He has cause to be so confident because of a sterling track record of successful procedures with advanced breakthrough technologies.

With my fears now assuaged, I am comfortable knowing I am in the hands of the very best healthcare team anywhere in the world.

The reality is, however, potentially rather grim especially at my age, 72 years old. The chances of cardiac arrest under anesthetic is very possible. In the face of this, I have requested that a DNR (do not resuscitate) be in place before surgery. I jokingly say “I do not want to come out of surgery talking like Rain Man”

I have visited with my priest and received three oils: the Oil of Catechumens (“Oleum Catechumenorum” or “Oleum Sanctorum“), the Oil of the Infirm (“Oleum Infirmorum“), and Holy Chrism (“Sacrum Chrisma“). So I am now in state of peaceful bliss and have made peace within myself through my faith in God and the support of some very special people who love me as much as I do them. May God bless us all.

Today I received a phone call from a dear sweet friend Alvaro. He had called to tell me he was praying for me and wished me “God speed.” After whining on in the most fatalistic tone about not wanting to be resuscitated should things go wrong during surgery, Alvaro simply said, ” Well, you should think about living until you are 90 or 100 years old.”

His tone was matter of fact. No nonsense, good, old-fashioned FAITH was his message, and it hit me like a ton of bricks how I was rather pessimistic about life when I should be celebrating every waking hour.

When I hung up, I felt wonderfully happy and absolutely renewed, and now I see things in a very different way thanks to some wise words from a very wise young man. Thank you, Alvaro.

The main right ventricle to my heart is so calcified that it cannot be penetrated by the normal use of a wire, so you all know the drill (another silly joke). Sometime in the next week or so, I will undergo a complex procedure with a special device for drilling at at angle using a razorback diamond drill hence, A Diamond In The Heart. and to make it even more interesting the operation will be done at a brand new facility UCSD Sulpizio Cardiovascular Center in La Jolla, CA.

When things could not look more rosy, enter Dr. Ehtisham Mahmud, an Irishman (obvious Irish joke) who is Chief of Cardiovascular Medicine, Director of Sulpizio Cardiovascular Center-Medicine, and Director of Interventional Cardiology. He is board-certified in cardiovascular medicine and interventional cardiology, and has extensive experience in complex coronary, renal, lower extremity and carotid interventions.

Under Dr. Mahmud’s leadership, the Interventional Cardiology program is among the largest academic interventional programs in the western United States. Dr. Mahmud directs the interventional clinical trials center; his research interests include investigational pharmacotherapies and devices used in cardiovascular interventions.

Dr. Mahmud completed fellowships in coronary and peripheral vascular interventions at Emory University in Atlanta and cardiovascular medicine at UC San Diego. He completed his internal medicine residency at UC San Diego and earned his medical degree at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada.

Dr. Mahmud is a fellow of the American College of Cardiology, Society of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, and the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. He has been voted one of the top physicians in San Diego by the San Diego county medical society and among the top 1 percent of interventional cardiologists in the nation by US News and World Report.

Dr. Mahmud is a Professor of Medicine at UCSD and Director, Cardiovascular Catheterization Laboratory and Interventional Cardiology at UCSD Medical Center. He has been honored with the Laennec Society Young Clinician Award from the American Heart Association and chosen as one of America’s Top Physicians each year from 2003 through 2009 by the Consumer Research Council. He is a Fellow of the Society of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, a Fellow of the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions, and a Fellow of the American College of Cardiology.

UPDATE:

The Dynamic Dou Dr Sharmi Mahmud and Dr Ali Salami, have just charted a new map of every single river and stream in the entire Amazon, and at the very same moment drilled out every single one of my calcified arteries and I feel like a new man.

After the procedure, Dr. Mahmud came to visit me, and as we chatted, it occurred to me that because the operation was so successful I felt compelled to tell him that he and Dr. Salami were so very good at this that they more than likely could get a job at any hospital. Dr Mahmud stared at me for a minute, then he said he would talk to Dr Salami, and perhaps they should both go for an interview together. I do hope they follow up because we need all the heart surgeons we can get.

Dr. Ehtisham Mahmud

Dr. William B. Davis

Dr. Paul Philips

Dr Ali Salami

Dr Bruce Kimura

John Marston 1576 – 1634 William Shakespeare 1564 – 1616

Freevill (to Franceschina): Go; y’are grown a punk rampant.

If your only exposure to Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is the 1968 Franco Zeffirelli film version, then you have been deceived! The language in the film is not 100% Shakespearean. In the case of the “punk rampant.” The phrase is actually from The Dutch Courtesan by John Marston, 1605: So it is authentically of Shakespeare’s era (or a tad later) and not Zeffirelli’s. But how modern is it! “Punk Rampant!” could describe any number of contemporary scurvy knaves.

John Marston married Mary Wilkes, daughter of one of the royal chaplains, and Ben Jonson said that ” Marston wrote his father-in-law’s preachings, and his father-in-law his sermons.” His first work was The Metamorphosis of Pigmalions Image, and certaine Satyres (1598). “Pigmalion” is an erotic poem in the metre of Venus and Adonis, and Joseph Hall attached a rather clumsy epigram to every copy that was exposed for sale in Cambridge. In the same year Marston published, under the pseudonym of W. Kinsayder, already employed in the earlier volume, his Scourge of Villanie, eleven satires, in the sixth of which he asserted that Pigmalion was intended to parody the amorous poetry of the time. Both this volume and its predecessor were burnt by order of the archbishop of Canterbury. The satires, in which Marston avowedly took Persius as his model, are coarse and vigorous. In addition to a general attack on the vices of his age he avenges himself on Joseph Hall who had assailed him in Virgidemiae.

He had a great reputation among his contemporaries. John Weever couples his name with Ben Jonson’s in an epigram; Francis Meres in Palladis tamia (1598) mentions him among the satirists; a long passage is devoted to “Monsieur Kinsayder” in the Return from Parnassus (1606), and Dr Brinsley Nicholson has suggested that Furor poeticus in that piece may be a satirical portrait of him. But his invective by its general tone, goes far to justify Mr W. J. Courthope’s1 judgment that “it is likely enough that in seeming to satirize the world without him, he is usually holding up the mirror to his own prurient mind.”

On the 28th of September 1599 Henslowe notices in his diary that he lent “unto Mr Maxton, the new poete, the sum of forty shillings,” as an advance on a play which is not named. Another hand has amended “Maxton” to” Mastone.” The earliest plays to which Marston’s name is attached are The History of Antonio and Mellida. The First Part; and Antonio’s Revenge. The Second Part (both entered at Stationers’ Hall in 1601 and printed 1602). The second part is preceded by a prologue which, in its gloomy forecast of the play, moved the admiration of Charles Lamb, who also compares the situation of Andrugio and Lucia to Lear and Kent, but the scene which he quotes gives a misleading idea of the play and of the general tenor of Marston’s work.

The melodrama and the exaggerated expression of these two plays offered an opportunity to Ben Jonson, who had already twice ridiculed Marston, and now pilloried him as Crispinus in The Poetaster (1600). The quarrel was patched up, for Marston dedicated his Malcontent (1604) to Jonson, and in the next year he prefixed commendatory verses to Sejanus. Far greater restraint is shown in The Malcontent than in the earlier plays. It was printed twice in 1604, the second time with additions by John Webster. The Dutch Courtezan (1605) and Parasitaster, or the Fawne (1606) followed. In 1605 Eastward Hoe, a gay comedy of London life, which gave offence to the king’s Scottish friends, caused the playwrights concerned in its production — Marston, Chapman and Jonson — to be imprisoned at the instance of Sir James Murray.

The Wonder of Women, or the Tragedie of Sophonisba (1606), seems to have been put forward by Marston as a model of what could be accomplished in tragedy. In the preface he mocks at those authors who make a parade of their authorities and their learning, and the next play, What you Will(printed 1607; but probably written much earlier), contains a further attack on Jonson. The tragedy of The Insatiate Countesse was printed in 1613, and again, this time anonymously, in 1616. It was not included in the collected edition of Marston’s plays in 1633, and in the Duke of Devonshire’s library there is a copy bearing the name of William Barksteed, the author of the poems, Myrrha, the Mother of Adonis (1607), and Hiren and the Fair Greek (1611). The piece contains many passages superior to anything to be found in Marston’s well-authenticated plays, and Mr A. H. Bullen suggests that it may be Barksteed’s version of an earlier one drafted by Marston.

The character and history of Isabella are taken chiefly from “The Disordered Lyfe of the Countess of Celant” in William Paynter’s Palace of Pleasure, derived eventually from Bandello. There is no certain evidence of Marston’s authorship in Histriomastix (printed 1610, but probably produced before 1599), or in Jacke Drums Entertainement, or the Comedie of Pasquil and Katherine (1616), though he probably had a hand in both. Mr R. Boyle (Englische Studien, vol. xxx., 1901), in a critical study of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, assigns to Marston’s hand the whole of the action dealing with Hector, with the prologue and epilogue, and attributes to him the bombast and coarseness in the last scenes of the play.

It will be seen that his undoubted dramatic work was completed in 1607. It is uncertain at what time he exchanged professions, but in 1616 he was presented to the living of Christchurch, Hampshire. He formally resigned his charge in 1631, and when his works were collected in 1633 the publisher, William Sheares, stated that the author “in his autumn and declining age” was living “far distant from this place.” Nevertheless he died in London, in the parish of Aldermanbury, on the 25th of June 1634. He was buried in the Temple Church.

Marston’s works were first published in 1633, once anonymously as Tragedies and Comedies, and then in the same year as Workes of Mr John Marston. The Works of John Marston (3 vols.) were reprinted by Mr J. O. Halliwell (Phillipps) in 1856, and again by Mr. A. H. Bullen (3 vols.) in 1887. His Poems (2 vols.) were edited by Dr A. B. Grosart in 1879.

JOHN MARSTON, English dramatist and satirist, eldest son of John Marston of Coventry, at one time lecturer of the Middle Temple, was born in 1575, or early in 1576. Swinburne notes his affinities with Italian literature, which may be partially explained by his parentage, for his mother was the daughter of an Italian physician, Andrew Guarsi. He entered Brasenose College, Oxford, in 1592, taking his B.A. degree in 1594. The elder Marston in his will expresses regret that his son, to whom he left his law-books and the furniture of his rooms in the Temple, had not been willing to follow his profession..

John Clare Poet 1793–1864

I ne’er was struck before that hour

John Donne Poet 1572–1631

John Donne’s standing as a great English poet, and one of the greatest writers of English prose, is now assured. However, it has been confirmed only in the early 20th century. The history of Donne’s reputation is the most remarkable of any major writer in English; no other body of great poetry has fallen so far from favor for so long and been generally condemned as inept and crude. In Donne’s own day his poetry was highly prized among the small circle of his admirers, who read it as it was circulated in manuscript, and in his later years he gained wide fame as a preacher. For some 30 years after his death successive editions of his verse stamped his powerful influence upon English poets. During the Restoration his writing went out of fashion and remained so for several centuries. Throughout the 18th century, and for much of the 19th century, he was little read and scarcely appreciated. Commentators followed Samuel Johnson in dismissing his work as no more than frigidly ingenious and metrically uncouth. Some scribbled notes by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in Charles Lamb‘s copy of Donne’s poems make a testimony of admiration rare in the early 19th century. Robert Browning became a known (and wondered-at) enthusiast of Donne, but it was not until the end of the 1800s that Donne’s poetry was eagerly taken up by a growing band of avant-garde readers and writers. His prose remained largely unnoticed until 1919.

In the first two decades of the 20th century Donne’s poetry was decisively rehabilitated. Its extraordinary appeal to modern readers throws light on the Modernist movement, as well as on our intuitive response to our own times. Donne may no longer be the cult figure he became in the 1920s and 1930s, when T. S. Eliot and William Butler Yeats, among others, discovered in his poetry the peculiar fusion of intellect and passion and the alert contemporariness which they aspired to in their own art. He is not a poet for all tastes and times; yet for many readers Donne remains what Ben Jonson judged him: “the first poet in the world in some things.” His poems continue to engage the attention and challenge the experience of readers who come to him afresh. His high place in the pantheon of the English poets now seems secure.

Donne’s love poetry was written nearly four hundred years ago; yet one reason for its appeal is that it speaks to us as directly and urgently as if we overhear a present confidence. For instance, a lover who is about to board ship for a long voyage turns back to share a last intimacy with his mistress: “Here take my picture” (Elegy 5). Two lovers who have turned their backs upon a threatening world in “The Good Morrow” celebrate their discovery of a new world in each other:

Let sea-discoverers to new worlds have gone,

Let maps to others, worlds on worlds have shown,

Let us possess one world, each hath one, and is one.

In “The Flea” an importunate lover points out a flea that has been sucking his mistress’s blood and now jumps to suck his; he tries to prevent his mistress from crushing it:

Oh stay, three lives in one flea spare,

Where we almost, nay more than married are.

This flea is you and I, and this

Our marriage bed, and marriage temple is;

Though parents grudge, and you, we’ are met,

And cloistered in these living walls of jet.

This poem moves forward as a kind of dramatic argument in which the chance discovery of the flea itself becomes the means by which they work out the true end of their love. The incessant play of a skeptical intelligence gives even these love poems the style of impassioned reasoning.

The poetry inhabits an exhilaratingly unpredictable world in which wariness and quick wits are at a premium. The more perilous the encounters of clandestine lovers, the greater zest they have for their pleasures, whether they seek to outwit the disapproving world, or a jealous husband, or a forbidding and deeply suspicious father, as in Elegy 4

, “The Perfume”

Though he had wont to search with glazed eyes,

As though he came to kill a cockatrice,

Though he have oft sworn, that he would remove

Thy beauty’s beauty, and food of our love,

Hope of his goods, if I with thee were seen,

Yet close and secret, as our souls, we have been.

Exploiting and being exploited are taken as conditions of nature, which we share on equal terms with the beasts of the jungle and the ocean. In “Metempsychosis” a whale and a holder of great office behave in precisely the same way:

He hunts not fish, but as an officer,

Stays in his court, as his own net, and there

All suitors of all sorts themselves enthral;

So on his back lies this whale wantoning,

And in his gulf-like throat, sucks everything

That passeth near.

Donne characterizes our natural life in the world as a condition of flux and momentariness, which we may nonetheless turn to our advantage, as in “Woman’s Constancy“:

Now thou hast loved me one whole day,

Tomorrow when thou leav’st, what wilt thou say?

…………………………………..

Vain lunatic, against these ‘scapes I could

Dispute, and conquer, if I would,

Which I abstain to do,

For by tomorrow, I may think so too.

In such a predicament our judgment of the world around us can have no absolute force but may at best measure people’s endeavors relative to each other, as Donne points out in “Metempsychosis”:

There’s nothing simply good, nor ill alone,

Of every quality comparison,

The only measure is, and judge, opinion.

The tension of the poetry comes from the pull of divergent impulses in the argument itself. In “A Valediction: Of my Name in the Window,” the lover’s name scratched in his mistress’s window ought to serve as a talisman to keep her chaste; but then, as he explains to her, it may instead be an unwilling witness to her infidelity:

When thy inconsiderate hand

Flings ope this casement, with my trembling name,

To look on one, whose wit or land,

New battery to thy heart may frame,

Then think this name alive, and that thou thus

In it offend’st my Genius.

So complex or downright contradictory is our state that quite opposite possibilities must be allowed for within the scope of a single assertion, as in Satire 3: “Kind pity chokes my spleen; brave scorn forbids / Those tears to issue which swell my eye-lids.”

The opening lines of Satire 3 confront us with a bizarre medley of moral questions: Should the corrupted state of religion prompt our anger or our grief? What devotion do we owe to religion, and which religion may claim our devotion? May the pagan philosophers be saved before Christian believers? What obligation of piety do children owe to their fathers in return for their religious upbringing? Then we get a quick review of issues such as the participation of Englishmen in foreign wars, colonizing expeditions, the Spanish auto-da-fé, and brawls over women or honor in the London streets. The drift of Donne’s argument holds all these concerns together and brings them to bear upon the divisions of Christendom that lead men to conclude that any worldly cause must be more worthy of their devotion than the pursuit of a true Christian life. The mode of reasoning is characteristic: Donne calls in a variety of circumstances, weighing one area of concern against another so that we may appraise the present claim in relation to a whole range of unlike possibilities: “Is not this excuse for mere contraries, / Equally strong; cannot both sides say so?” The movement of the poem amounts to a sifting of the relative claims on our devotion that commonly distract us from our absolute obligation to seek the truth.

Some of Donne’s sharpest insights into erotic experience, as his insights into social motives, follow out his sense of the bodily prompting of our most compelling urges, which are thus wholly subject to the momentary state of the physical organism itself. In “Farewell to Love” the end that lovers so passionately pursue loses its attraction at once when they have gained it:

Being had, enjoying it decays:

And thence,

What before pleased them all, takes but one sense,

And that so lamely, as it leaves behind

A kind of sorrowing dullness to the mind.

Yet the poet never gives the impression of forcing a doctrine upon experience. On the contrary, his skepticism sums up his sense of the way the world works.

Donne’s love poetry expresses a variety of amorous experiences that are often startlingly unlike each other, or even contradictory in their implications. In “The Anniversary” he is not just being inconsistent when he moves from a justification of frequent changes of partners to celebrate a mutual attachment that is simply not subject to time, alteration, appetite, or the sheer pull of other worldly enticements:

All kings, and all their favourites,

All glory of honours, beauties, wits,

The sun itself, which makes times, as they pass,

Is elder by a year, now, than it was

When thou and I first one another saw:

All other things, to their destruction draw,

Only our love hath, nor decay;

This, no tomorrow hath, nor yesterday,

Running it never runs from us away,

But truly keeps his first, last, everlasting day.

The triumph the lovers proclaim here defies the state of flux it affirms.

Some of Donne’s finest love poems, such as “A Valediction: forbidding Mourning,” prescribe the condition of a mutual attachment that time and distance cannot diminish:

Dull sublunary lovers’ love

(Whose soul is sense) cannot admit

Absence, because it doth remove

Those things which elemented it.

But we by a love, so much refined,

That our selves know not what it is,

Inter-assured of the mind,

Care less, eyes, lips, and hands to miss.

Donne finds some striking images to define this state in which two people remain wholly one while they are separated. Their souls are not divided but expanded by the distance between them, “Like gold to airy thinness beat”; or they move in response to each other as the legs of twin compasses, whose fixed foot keeps the moving foot steadfast in its path:

Such wilt thou be to me, who must

Like th’ other foot obliquely run;

Thy firmness makes my circle just,

And makes me end, where I begun.

A supple argument unfolds with lyric grace.