By: Alan Graham

One of the most tragic stories concerning intimacy in humans is the forlorn tale of sadness concerning the lack of such between Kenneth Grahame the writer of Wind in the Willows, and his son Alistair.

All the gold on earth cannot bring joy if that “caring gene” does not exist within oneself, but to decry or to indict someone for not displaying it to others is a lesson in futility.

They, as do we all, come hard wired from the womb/factory, be it eye, hair, or skin color, angry, sad, depressed or happy, the human is delivered as surely as a car from the factory, with preset conditions, and some run smoothly while others malfunction or breakdown often.

‘Monday’s Child,’ a poem/nursery rhyme which dates back to the early 1500s is illustrative of the different types of personalities, sad, happy, angry, worried, all dictated by the genetic code issued in the womb at the moment of conception.

Tragedy in the Willows

Hidden in a quiet corner of Oxford, in the shadow of medieval St Cross Church, stands a moving pair of gravestones.

In one of them lies one of the most beloved names in English literature, Kenneth Grahame, writer of The Wind in The Willows, the bewitching riverbank tale of Mole, Ratty and Toad of Toad Hall. In the other lies his son, Alastair, nicknamed Mouse.

What could be more comforting? — father and son resting together by an ancient church nestling beside the River Thames, the setting for Grahame’s gentle masterpiece.

Cold relationship: Kenneth Grahame often ignored pleas to visit his son Alastair at boarding school – and never recovered when he committed suicide aged just 19

And yet, look closer at those graves, and a tragic tale begins to emerge. Kenneth Grahame died in 1932, a broken-hearted man of 73, who hadn’t written anything of note since The Wind in The Willows was published in 1908.

The reason for his heartbreak lies next to him — Mouse committed suicide 12 years before his father’s death, aged only 19.

Despite a glittering education at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, Mouse, a frail child, blind in one eye, was of a fragile, nervous disposition. His father’s immense fame — and unrealistic expectations of his son — didn’t make things any easier.

And so, one evening in May 1920, after dining in Christ Church’s 16th century hall, Mouse strolled down to the Thames — home of Ratty, Toad and Mole. And there he lay down on the railway track running across Port Meadow and awaited the train that would end his misery.

Now this sad tale of tortured paternal love has come to the surface once more, with this week’s sale of a signed first edition of The Wind in The Willows for £40,000 — five times the estimate.

The dedicatee of the book is Ruth Ward, a childhood friend of Mouse. Also in this week’s sale is a rare picture of Mouse — a chubby-cheeked cherub of a boy — and several letters to Ruth Ward from the writer’s wife, Elspeth.

Writing in 1908, Elspeth says: ‘I thought you might like perhaps better than anything else a new book that Mouse’s Daddy has just written, so I asked him for one for your birthday present. I want to know how you like it. Mouse is having it read to him every evening and is greatly pleased with it.’

The letter paints a picture of a close young family — Mouse was eight at the time — but the sad truth is that, despite the enormous success of The Wind In The Willows, the Grahame household was not happy.

For all his fame and fortune, Grahame remained a tortured soul until his death. Several weeks after his funeral, his coffin was moved to the Oxford cemetery from its grave in Pangbourne, Berks.

Grahame was born in 1859 in Edinburgh to an aristocratic, failed lawyer, whose love for poetry was defeated by his love for vintage claret. The drinking only intensified when Grahame’s mother, Bessie, died soon after the birth of his brother, Roland.

Grahame was only five — his place in the world grew even more insecure when, weeks after the death, his father moved the family to Cookham Dene in Berkshire on the banks of the Thames. Grahame clung to the river for the rest of his life.

The young Grahame excelled at school and was set for high academic honours when another hammer blow struck. The family finances had dwindled so much that he was forced straight into work at the Bank of England.

For the next 30 years, he toiled away at the Bank, retiring as its Secretary in 1908, the year of The Wind in The Willows. Throughout his career, he had published children’s books and a memoir of childhood — sales were good, and Grahame was well-known before his worldwide smash hit was published.

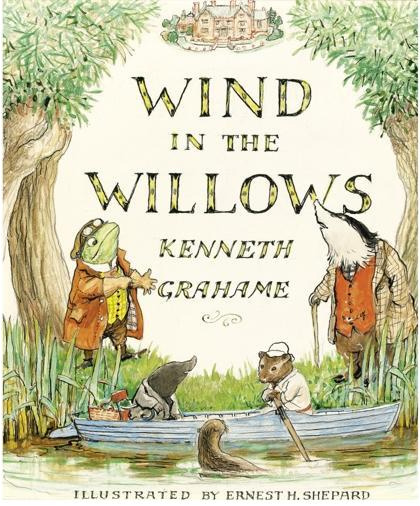

Still a favourite: Kenneth Grahame’s tails of Mole, Toad and Ratty have engrossed children for generations

Despite his eligibility as a literary banker, Grahame remained awkward in the company of the opposite sex. It wasn’t until he was 40 that he married Elspeth Thomson. For all her devotion to him, he remained a distant figure, incapable of demonstrating love.

The same emotional constipation condemned his relationship with poor Mouse, born in 1900. A little premature, Mouse was blind in his right eye; the other had a severe squint.

As an only child, Mouse was subjected to extreme, uncritical affection from his mother, and absurdly high academic expectations from his father. It didn’t help that Elspeth was growing increasingly miserable, taking to her bed for much of the day.

By the time he was three and a half, in a haunting prophecy of his death, Mouse amused himself playing a game of lying in front of speeding cars to bring them screeching to a halt. When he was given his presents on his fourth birthday, rather than enjoying them, he set about repacking them in complete silence.

All the while, though, this sad, pressured little boy was inadvertently helping the creation of one of the great children’s books, a book which is full of a brand of carefree happiness that always dodged Mouse himself.

Grahame was inspired to write The Wind In The Willows by the bedtime stories he read his son. One evening, when Mouse was four, his parents were due to go out for dinner. Waiting for her husband in the hall, Elspeth sent the maid for him.

‘He’s with Master Mouse, madam,’ said Louise, the maid, ‘He’s telling him some ditty about a toad.’ Grahame took to transcribing verbatim accounts of the stories, written in the same baby-talk that he had told them. ‘The Mole saved up al is money and went and bought a motor car… Mr Mole has been goin the pace since he first went [on] his simple boatin spedishin wif the Water Rat.’

The publication of The Wind in The Willows, though, did nothing to stop the boy’s awful downward trajectory.

Bullied at Rugby School, Mouse was transferred to Eton. There, too, he suffered because of his disastrously superior attitude. He left the school to be privately tutored in Surrey.

His eyesight worsening, and his nerves still tattered, it was a broken, miserable Mouse, then, that turned up at Christ Church in 1918. He failed his scripture, Greek and Latin exams three times over the next year. In 1919, his tutor wrote the words ‘Pass or go’ next to his name in the college records; if he failed the exam again, he would have to leave.

He had made no friends and joined no social clubs. It had all got too much for him. At that last dinner in Christ Church Hall, he downed a glass of port. An undergraduate sitting next to him said later, ‘I had not known him do [this] before.’

Mouse then trudged off across Port Meadow towards the railway track. When his decapitated body was found the next day, his pockets were crammed with religious books for his dreaded scripture exam.

His death did at least bring one consolation; in recognition of his suffering, Oxford University, for the first time, made special provision for disabled students.

On May 12, 1920, Mouse’s 20th birthday, he was buried in Holywell Cemetery next to St Cross Church. His father scattered lilies of the valley over the coffin.

And 12 years later, the shattered genius who wrote The Wind in The Willows was buried beside the doomed little boy who had inspired him.

Cold relationship:

Kenneth Grahame often ignored pleas to visit his son Alastair at boarding school – and never recovered when he committed suicide aged just 19